Abstract

Background

Eliciting patient concerns and listening carefully to them contributes to patient-centered care. Yet, clinicians often fail to elicit the patient’s agenda and, when they do, they interrupt the patient’s discourse.

Objective

We aimed to describe the extent to which patients’ concerns are elicited across different clinical settings and how shared decision-making tools impact agenda elicitation.

Design and Participants

We performed a secondary analysis of a random sample of 112 clinical encounters recorded during trials testing the efficacy of shared decision-making tools.

Main Measures

Two reviewers, working independently, characterized the elicitation of the patient agenda and the time to interruption or to complete statement; we analyzed the distribution of agenda elicitation according to setting and use of shared decision-making tools.

Key Results

Clinicians elicited the patient’s agenda in 40 of 112 (36%) encounters. Agendas were elicited more often in primary care (30/61 encounters, 49%) than in specialty care (10/51 encounters, 20%); p = .058. Shared decision-making tools did not affect the likelihood of eliciting the patient’s agenda (34 vs. 37% in encounters with and without these tools; p = .09). In 27 of the 40 (67%) encounters in which clinicians elicited patient concerns, the clinician interrupted the patient after a median of 11 seconds (interquartile range 7–22; range 3 to 234 s). Uninterrupted patients took a median of 6 s (interquartile range 3–19; range 2 to 108 s) to state their concern.

Conclusions

Clinicians seldom elicit the patient’s agenda; when they do, they interrupt patients sooner than previously reported. Physicians in specialty care elicited the patient’s agenda less often compared to physicians in primary care. Failure to elicit the patient’s agenda reduces the chance that clinicians will orient the priorities of a clinical encounter toward specific aspects that matter to each patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The medical interview is a pillar of medicine. It allows patients and clinicians to build a relationship.1 Ideally, this process is inherently therapeutic, allowing the clinician to convey compassion, and be responsive to the needs of each patient.2,3 Eliciting and understanding the patient’s agenda enhances and facilitates patient-clinician communication.2,3 Agenda setting is a conversational strategy that allows clinicians and patients to negotiate and collaborate to clarify the concerns and expectations of both parties. This results in a constructive alliance that leads to focused, efficient, and patient-centered care.4,5 A review of the literature, evaluating communication and relationship skills, identified six studies in general clinical practice, in which setting the patient’s agenda enhanced communication efficiency.5 However, despite these potential benefits, the use of this communication skill in general clinical practice appears to be limited. In a landmark clinical communication study published in 1984, Beckman et al. found that in 69% of the visits to a primary care internal medicine practice, the physician interrupted the patient, with a mean time to interruption of 18 s.6 Fifteen years later, Marvel et al. found that physicians solicited the patient’s concern in 75% of primary care visits and interrupted this initial statement in a mean of 23 s.7 Similarly, Dyche et al. found in 2004 that in approximately 60% of general medicine visits, the clinician inquired about the patient’s agenda, that only 26% of the patients completed their statement uninterrupted, and that the mean time to interruption was 16.5 s. In addition, failure to elicit the patients’ agenda was associated with a 24% reduction in the physician’s understanding of the main reasons for the consultation.8 Although the prevalence of agenda setting has been studied in general medicine clinics, the prevalence of agenda setting in specialty care remains relatively unexplored. One study evaluating psychiatric consultations found agenda inquiries in 90% of these visits, with 67% of these proceeding without interruption.9 These studies, performed decades apart, suggest that clinicians often fail to elicit the patient’s agenda and when they do, they promptly interrupt patients.

Patient-centeredness is considered an important dimension of health care quality. It describes a culture where a partnership among practitioners, patients, and their families is established to ensure medical decisions respect patients’ wants, needs, and preferences, and that patients have the education and support they require to make medical decisions and participate in their own care.10 Shared decision-making (SDM) is a process that enables patient-centeredness.2,11,12 Patients and clinicians, who engage in SDM, work together to understand the patient’s situation and determine the best course of action to address it. In this process, an important first step is for patients and clinicians to determine which problems require attention through collaborative conversations.13,14 Patient decision aids and conversation aids are tools that can support SDM. They often provide a summary of the clinical evidence regarding a medical decision and relevant clinical management options.13 A systematic review of 105 randomized trials of SDM tools found that they improved patient knowledge and risks perception, helped patients clarify their values, and increased the proportion of patients involved in medical decision-making.11 Although, these SDM tools, particularly conversation aids, are designed to support treatment and diagnostic conversations between patients and clinicians; their impact on other aspects of patient-centeredness, such as agenda setting, has not been studied directly. Clearly identifying the presence of alternatives to deal with a clinical situation is considered an important step for SDM, and agenda setting could be associated with this step. Kunneman et al. evaluated 100 encounters between rectal/breast cancer patients, and their clinicians and found that only in 3% of the encounters, the clinician set a treatment choice agenda.15 Moreover, in a secondary analysis of studies evaluating SDM, clinicians indicated a treatment choice agenda in 44% of the encounters without SDM tools versus 62% in those where SDM tools were used (p = .34).16

To our knowledge, there is no current assessment of the prevalence of agenda setting in general and specialty practice despite substantial changes to the clinical encounter and to the definition of high-quality medical care. For example, time constraints and the use of electronic medical records can hinder patient-clinician interaction. Patient-facing interactions (in contrast to computer-facing ones) account for about 50% of the clinical time, potentially limiting the opportunity for agenda setting conversations and promoting more frequent interruptions.17,18,19 On the other hand, policymakers have emphasized the importance of patient-centeredness and of SDM in high-quality care, activities that may start from setting a patient-focused agenda.10,17,19

The objectives of this study were to determine the frequency of encounters in which clinicians elicited the patient’s agenda, the proportion and timing of interrupted answers, and the effect of SDM tools and clinical setting on these outcomes.

METHODS

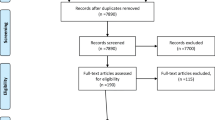

We performed a secondary analysis of clinical encounters recorded as part of practice-based trials that examined the effect of SDM tools published between 2008 and 2015.20,21,22,23,24,25,26 These trials were conducted in general practices in Minnesota and Wisconsin and at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota and affiliated clinics. The SDM tools that were tested supported conversations regarding treatment options for Grave’s disease, depression, osteoporosis, diabetes, and cardiovascular prevention (use of statins). Approximately, 300 clinicians with access to electronic medical records and 700 patients were enrolled. Sixty-six senior clinicians were included in this secondary analysis and most participated in only one of the included encounters (74%; Table 1). Of the 272 recordings available for analyses from these trials, we included all the complete clinical encounters that were recorded in specialty care (51 videos) and selected a random sample of 75 visits from the 221 remaining primary care videos stratified by treatment arm (SDM vs usual care) of which only 61 were complete, resulting in an analysis of 112 videos.

Study Outcomes and Definitions

The main outcome of this secondary analysis was the proportion of encounters in which the patient’s agenda was elicited. In cases where more than one clinician evaluated the patient, elicitation of the patient’s agenda noted by any of the evaluators was considered valid. We based our coding on the work by Beckman and Marvel.6 We defined agenda elicitation as the clinician making a declarative statement around the patient’s reason for the visit or an introductory question resulting in disclosure of the patient agenda, e.g., What can I do for you today? What is your main concern? Tell me what brings you in today?6,7

If the patient’s agenda was elicited, we determined whether the clinician interrupted the patient discourse or not. If completed (uninterrupted), we recorded the length of the statement and if interrupted, the time to interruption. A completed statement was indicated by the patient marking his own statement as completed (e.g., “that is all”), asking a concern-related question to the physician, or explicitly declining to offer further information (e.g., after a clinicians asks “anything else?”).6,7 The following were considered interruptions if they resulted in incomplete patient statements: closed-ended questions, the use of an elaborator (e.g., tell me more about this pain), a re-completer (restating the content), or a statement (non-interrogative utterance that halted or redirected the patient’s narrative).6,7 (Appendix)

Data Collection

Using Noldus Observer XT software (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen—The Netherlands), we evaluated and coded audio and video-recordings from each encounter.27 Additional information about each encounter was recorded with the use of a standardized evaluation form in REDCAP.28

Four experienced reviewers (N.S.O., K.P., R.R.G., A.C.G.), working independently, analyzed the recordings in duplicate. Initially, all reviewers evaluated 12 videos and discussed their findings toward achieving calibration and to resolve disagreements. When the chance-adjusted interobserver agreement reached 82%, reviewers proceeded with the full analysis. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third party (research team member who had not previously evaluated the encounter in dispute).

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were calculated according to variable type and distribution. For the analysis of time to interruption or to completed statement, we obtained an average from the time reported by each of the two reviewers that coded the video and used this average for summary statistics. Comparisons between groups were analyzed using the cluster adjusted X2 statistic, accounting for clustering by the research study that produced the video, thus accounting for the intra-clustering coefficient.29 Statistical analyses were performed using JMP and STATA.30

RESULTS

A total of 112 medical encounters were reviewed (87 [78%] audio-video and 25 [22%] audio-only), with a median encounter duration of 30 min (range 4 to 80) Table 2. Medical encounters in which the patient’s agenda was elicited were longer than those in which it was not (Table 2). In 34 encounters (30%), a physician in training interviewed the patient first. The patient’s agenda was elicited in 40 encounters (36%). In 13 encounters (33%), the agenda was elicited more than once. Most commonly, the agenda was elicited during the opening of the encounter (77%), and less often during counseling (20%) and data gathering (3%).

In primary care clinics, the agenda was elicited in 30/61 encounters (49%) compared to 10/51 (20%) in specialty care clinics; p = 0.058. Of the 30 primary care encounters where the agenda was elicited, physicians interrupted the patients in 19 (63%). Of the 10 encounters in specialty care where the agenda was elicited, physicians interrupted patients in 8 (80%).

The percentage of encounters in which the agenda was elicited did not change based on the use of an SDM tool (Table 2).

Physicians interrupted the patient in 27 of the 40 (67%) encounters in which the agenda was elicited. The median time to interruption was 11 s (interquartile range 7–22; range 3 to 234). When not interrupted, patients completed their agenda in a median of 6 s (interquartile rage 3–19; range 2 to 108 s). Most commonly, the physician interrupted by asking a closed-ended question (59%), followed by making a statement (30%), and using a re-completer (7%), or an elaborator (4%).

DISCUSSION

The patient’s agenda was elicited in 36% of the clinical encounters. Among those in which the agenda was elicited, patients were interrupted seven out of ten times, with a median time to interruption of 11 s. When left uninterrupted, patients completed their statements in a median of 6 s. Agenda elicitation was more common and less interrupted in primary than in specialty care. The use of SDM tools did not have an impact on agenda elicitation nor completion.

In comparison with previous literature,6,7,8 the proportion of medical encounters in our sample in which clinicians elicited the patient agenda was not better: 40 to 75% in the literature, 36% overall, and 50% in primary care in our sample. We found that interruptions occur extremely early in the patient’s discourse and that patients are given just a few seconds to tell their story. Previous studies have shown that when allowed to describe their concerns, most patients complete spontaneous talking in a mean of 92 s.31,32 Our estimate is much briefer perhaps because many completed statements correspond to patients indicating that they had no concerns. It is possible that the frequency of interruptions is not only dependent on physicians’ practices but also related to the complexity of each patient. Moreover, it can be argued that if done respectfully and with the patient’s best interest in mind, interruptions to the patient’s discourse may clarify or focus the conversation, and thus be beneficial to patients.33 Yet, it seems rather unlikely that an interruption, even to clarify or focus, could be beneficial at such early stage in the encounter.34

The elicitation of the patient perspective allows the clinician and patient to engage in meaningful conversations, thereby laying the foundation for patient-centered care and SDM. We did not find a difference in the prevalence of agenda setting in encounters without or without SDM tools. The specificity of the SDM tools (about a specific treatment decision) likely had no impact on the overall goal and general approach to the visit. This finding may also be related to timing: eliciting the patient’s agenda usually occurs at the beginning of the consultation, while SDM takes place towards its end.

Our study was a secondary analysis of clinical studies evaluating the effects of SDM tools. As a result, our findings may systematically differ from usual outpatient visits. Moreover, we were not able to perform subgroup analyses according to clinician characteristics. However, we evaluated the distribution of agenda setting in different clinical settings and according to use of SDM tools. Our evaluations were conducted in duplicate and with the use of a video analysis software to calculate time intervals; these methods likely contributed to reproducible judgments and improved accuracy, respectively.

Multiple barriers to patient-centered care could explain our results, including time constraints, limited education about patient communication skills, or physician burnout. We found that primary care clinicians were more likely to elicit the patient agenda than specialists, the latter perhaps focused on a specific problem, e.g., the reason for referral, and thus skipping this step. However, we would argue that even in a specialty visit that is presumed to be about one particular agenda item (e.g., management of Grave’s disease), it is invaluable to understand why the patient thinks they are at the appointment and what specific concerns they have related to the condition or its management.

Further studies should explore the relationship between agenda elicitation and patient experience and outcomes; the results of such studies may fuel research to continue to improve patient-clinician communication and remove encounter elements—such as the demands for entry the electronic health record makes, visit duration, and the proliferation of expected agenda items the healthcare system mandates—that clutter, interrupt, and disrupt the clinical encounter.35

In the meantime, the results of our study suggest that we are far from achieving patient-centered care, as barriers for adequate communication and partnership continue to limit the elicitation of the patient’s agenda and lead to quick interruptions of the patient discourse.

References

Cole SA, Bird J. The Medical Interview : The Three Function Approach. Third edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013.

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001.

Scholl I, Zill JM, Harter M, Dirmaier J. An integrative model of patient-centeredness—a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107828.

Gobat N, Kinnersley P, Gregory JW, Robling M. What is agenda setting in the clinical encounter? Consensus from literature review and expert consultation. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:822–9.

Mauksch LB, Dugdale DC, Dodson S, Epstein R. Relationship, communication, and efficiency in the medical encounter: creating a clinical model from a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1387–95.

Beckman HB, Frankel RM. The effect of physician behavior on the collection of data. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:692–6.

Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, Beckman HB. Soliciting the patient’s agenda: have we improved? JAMA. 1999;281:283–7.

Dyche L, Swiderski D. The effect of physician solicitation approaches on ability to identify patient concerns. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:267–70.

Frankel RM, Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Oles SK, Matthias MS. Agenda setting in psychiatric consultations: an exploratory study. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2013;36:195–201.

Hurtado MP, Swift EK, Corrigan JM, Institute of Medicine. Envisioning the National Health Care Quality Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001.

Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431.

Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Gionfriddo MR, Ospina NS, et al. Shared decision making in endocrinology: present and future directions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:706–16.

Montori VM, Kunneman M, Brito JP. Shared decision making and improving health care: the answer is not in. JAMA. 2017;318:617–8.

Montori VM, Kunneman M, Hargraves I, Brito JP. Shared decision making and the internist. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;37:1–6.

Kunneman M, Engelhardt EG, Ten Hove FL, et al. Deciding about (neo-)adjuvant rectal and breast cancer treatment: missed opportunities for shared decision making. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:134–9.

Kunneman M, Branda M, Hargraves I, Pieterse HM, Montori V. Fostering choice awareness for shared decision making: a secondary analysis of video-recorded clinical encounters. Mayo Clin Proc Inn Qual Out. 2018;2:60–8.

Poissant L, Pereira J, Tamblyn R, Kawasumi Y. The impact of electronic health records on time efficiency of physicians and nurses: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12:505–16.

Tai-Seale M, Olson CW, Li J, et al. Electronic health record logs indicate that physicians split time evenly between seeing patients and desktop medicine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36:655–62.

Walsh SH. The clinician’s perspective on electronic health records and how they can affect patient care. BMJ. 2004;328:1184–7.

Brito JP, Castaneda-Guarderas A, Gionfriddo MR, et al. Development and pilot testing of an encounter tool for shared decision making about the treatment of Graves’ disease. Thyroid. 2015;25:1191–8.

LeBlanc A, Herrin J, Williams MD, et al. Shared decision making for antidepressants in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1761–70.

LeBlanc A, Wang AT, Wyatt K, et al. Encounter decision aid vs. clinical decision support or usual care to support patient-centered treatment decisions in osteoporosis: the osteoporosis choice randomized trial II. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128063.

Montori VM, Shah ND, Pencille LJ, et al. Use of a decision aid to improve treatment decisions in osteoporosis: the osteoporosis choice randomized trial. Am J Med. 2011;124:549–56.

Shah ND, Mullan RJ, Breslin M, Yawn BP, Ting HH, Montori VM. Translating comparative effectiveness into practice: the case of diabetes medications. Med Care. 2010;48:S153–8.

Mullan RJ, Montori VM, Shah ND, et al. The diabetes mellitus medication choice decision aid: A randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1560–8.

Nannenga MR, Montori VM, Weymiller A, et al. A treatment decision aid may increase patient trust in the diabetes specialist. The Statin Choice randomized trial. Health Expect. 2009:12:38–44.

Michie S, Dormandy E, Marteau TM. The multi-dimensional measure of informed choice: a validation study. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:87–91.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81.

Kreft IGG, de Leeuw J. Introducing Multilevel Modeling. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1998.

Bünemann C. Chenot JF, Blank W. Further education on general medicine? A decision aid for medical students. Z Allgemeinmed. 2008; 84: 532–372009.

Langewitz W, Denz M, Keller A, Kiss A, Ruttimann S, Wossmer B. Spontaneous talking time at start of consultation in outpatient clinic: cohort study. BMJ. 2002;325:682–3.

Rabinowitz I, Luzzati R, Tamir A, Reis S. Length of patient’s monologue, rate of completion, and relation to other components of the clinical encounter: observational intervention study in primary care. BMJ. 2004;328:501–2.

Mauksch LB. Questioning a taboo: physicians’ interruptions during interactions with patients. JAMA. 2017;317:1021–2.

Phillips KA, Ospina NS. Physicians interrupting patients. JAMA. 2017;318:93–4.

Montori VM. Why We Revolt. A Patient Revolution for Careful and Kind Care. Rochester, NY: The Patient Revolution; 2017.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Jonathan Inselman’s assistance in identifying eligible video encounters for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Naykky Singh Ospina and Kari A. Phillips contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 12 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singh Ospina, N., Phillips, K.A., Rodriguez-Gutierrez, R. et al. Eliciting the Patient’s Agenda- Secondary Analysis of Recorded Clinical Encounters. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 36–40 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4540-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4540-5