Abstract

Objective

To establish whether a nationally guided programme can lead to more widespread implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS), a well-established optimised care pathway for lower limb arthroplasty.

Design

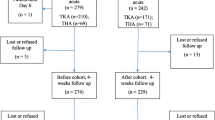

In 2010, National Services Scotland’s Musculoskeletal Audit was asked to perform a ‘snapshot’ audit of the current peri-operative management of patients undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty in all 22 Scottish orthopaedic units with an identical follow-up audit in 2011 after input and support from the national steering group.

Population

Audit 1 and audit 2 involved 1,345 and 1,278 patients, respectively.

Results

The number of Scottish units that developed an ERAS programme increased from 8 (36 %) to 15 (68 %). Units that included more ERAS patients had earlier mobilisation rates (146/474, 36 % ERAS patients mobilised same day vs. 34/873, 4 % non-ERAS; n = 22 units, r = 0.55, p = 0.008) and shorter post-operative length of stay (median 4 days vs. ERAS, 5 days non-ERAS, n = 22 units, r = −0.64, p = 0.001). ERAS knee arthroplasty patients had lower blood transfusion rates (5/205, 2 % vs. 51/399, 13 %, n = 22 units, r = −0.62, p = 0.002). Units that restricted the use of IV fluids post-operatively had higher early mobilisation rates (n = 22 units, r = 0.48, p = 0.03) and shorter post-operative length of stay (n = 22 units, r = −0.56, p = 0.007). Reduced use of patient-controlled analgesia was also associated with earlier mobilisation (n = 22 units, r = 0.49, p = 0.02) and shorter length of stay (n = 22 units, r = −0.39, p = 0.07). Urinary catheterisation rates also dropped from 468/1,345 (35 %) in 2010 to 337/1,278 (26 %) in 2011 (n = 22 units, z = 2.19, p = 0.03).

Conclusion

A clinically guided and nationally supported process has proven highly successful in achieving a further uptake of enhanced recovery principles after lower limb arthroplasty in Scotland, which has resulted in clinical benefits to patients and reduced length of hospital stay.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ethgen O, Bruyère O, Richy F, Dardennes C (2004) Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 86-A(5):963–974

Malchau H, Garellick G, Eisler T, Kärrholm J, Herberts P (2005) Presidential guest address: the Swedish hip registry: increasing the sensitivity by patient outcome data. Clin Orthop Relat Res 441:19–29

Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, Bach-Dal C, Rud K, Andersen KL et al (2006) Length of stay in total hip and knee arthroplasty in Denmark I: volume, morbidity, mortality and resource utilization. A national survey in orthopaedic departments in Denmark. Ugeskr Laeger 168(22):2139–2143

Schneider M, Kawahara I, Ballantyne G, McAuley C, Macgregor K, Garvie R et al (2009) Predictive factors influencing fast track rehabilitation following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 129(12):1585–1917

McDonald DA, Siegmeth R, Deakin AH, Kinninmonth AWG, Scott NB (2012) An enhanced recovery programme for primary total knee arthroplasty in the United Kingdom—follow up at one year. The Knee 19(5):525–529

Kehlet H (2006) Future perspectives and research initiatives in fast-track surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 391(5):495–498

Ayalon O, Liu S, Flics S, Cahill J, Juliano K, Cornell CN (2011) A multimodal clinical pathway can reduce length of stay after total knee arthroplasty. HSSJ 7(1):9–15

Juliano K, Edwards D, Spinello D, Capizzano Y, Epelman E, Kalowitz J et al (2011) Initiating physical therapy on the day of surgery decreases length of stay without compromising functional outcomes following total hip arthroplasty. HSSJ 7(1):16–20

Department of Health Guidance. Delivering enhanced recovery: helping patients get better sooner after surgery. Published 31st March 2010 on the Department of Health Website

Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, Bach-Dal C, Rud K, Andersen KL et al (2010) What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 130(2):263–268

Ogonda L, Wilson R, Archbold P, Lawlor M, Humphreys P, O’Brien S et al (2005) A minimal-incision technique in total hip arthroplasty does not improve early postoperative outcomes. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87(4):701–710

Khanna A, Gougoulias N, Longo UG, Maffulli N (2009) Minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Orthop Clin North Am 40(4):479–489

Cook TM, Counsell D, Wildsmith JA (2009) Royal College of Anaesthetists third national audit project. Major complications of central neuraxial block: report on the third national audit project of the Royal College of Anaesthetist. Royal College of Anaesthetists third national audit project. BJA 102(2):179-90

Chang C-C, Lin H-C, Lin H-W, Lin H-C (2010) Anesthetic management and surgical site infections in total hip or knee replacement: a population-based study. Anesthesiology 113:279–284

Grocott MP, Mythen MG, Gan TJ (2005) Perioperative fluid management and clinical outcomes in adults. Anesth Analg 100(4):1093–1106

Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, Curley C, Dahl OE, Schulman S et al (2012) Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 141(2 Suppl):e278S–e325S

Doherty M, Buggy DJ (2012) Intraoprative fluids: how much is too much. BJA 109(1):69–79

Iorio R, Whang W, Healy WL, Patch DA, Najibi S, Appleby D (2005) The utility of bladder catheterization in total hiparthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 432:148–152

Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Orsnes T, Wong C, Kehlet H (2010) Low risk of thromboembolic complications after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 81(5):599–605

Richman JM, Liu SS, Courpas G, Wong R, Rowlingson AJ, McGready J et al (2006) Does continuous peripheral nerve block provide superior pain control to opioids? A meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 102:248–257

Andersen LO, Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Kehlet H (2008) High-volume infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 52(10):1331–1335

Wu CL, Liu SS (2009) Neural blockade: impact on outcome. In cousins and Bridenbaugh’s neural blockade in clinical anesthesia and pain management, Fourth Edn. Lippincott Williams and Wilkin, Philadelphia

Lehmann M, Monte K, Barach P, Kindler CH (2010) Postoperative patient complaints: a prospective interview study of 12,276 patients. J Clin Anesth 22(1):13–21

Kerger KH, Mascha E, Steinbrecher B, Frietsch T, Radke OC, Stoecklein K, IMPACT Investigators et al (2009) Routine use of nasogastric tubes does not reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 109(3):768–773

Husted H, Lunn TH, Troelsen A, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen BB, Kehlet H (2011) Why still in hospital after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 82(6):679–684

Conflict of interest

None of the authors is aware of any competing interests. We wish to declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scott, N.B., McDonald, D., Campbell, J. et al. The use of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) principles in Scottish orthopaedic units—an implementation and follow-up at 1 year, 2010–2011: a report from the Musculoskeletal Audit, Scotland. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 133, 117–124 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-012-1619-z

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-012-1619-z